A Look at Fire Adapted Ecosystems in the Sierra Nevada

Forests of the Sierra Nevada have evolved with fire, as is evident in Sierran tree species characteristics, landscape scale fire histories, and the cultural history of these forests. Now, these same forests face the consequences of over a century of fire suppression that has resulted in a buildup of fuels and, in the worst cases, high-intensity wildfires that burn tens of thousands of acres. With great effort, decision-makers and stewards of the land are working to restore fire to the landscape in a way that supports fire resilient ecosystems and reduces the risk of high-intensity wildfire.

An Evolving Narrative

For over a century, the prevailing story of fire has been about prevention. Many of us grew up with stories that oversimplified wildfire as a universally bad thing and failed to differentiate types of fires. The scene in Disney’s Bambi wherein the deer were forced to flee their home, for example, may have inspired fear of fire. Perhaps Smokey the Bear visited your fourth grade class to teach about the importance of fire prevention. These depictions of fire, however, fail to recognize its vital role in the Sierra Nevada.

The European colonization of the Americas that brought the notion that all fire is bad and must be extinguished caused major problems. In places like the Sierra Nevada, where fire had been a part of the landscape for thousands of years, suddenly lightening-ignited fires and all cultural burning by Indigenous peoples was either suppressed as fast as possible or banned all together. Although the idea of fire suppression was well-intentioned at the time, much of the Sierra Nevada and California now are facing the consequences of these actions. Fire fuels have built up and are making the forests vulnerable to catastrophic wildfire.

Finally, after years of scientific reports and successful restoration efforts, the narrative around fire is shifting from a disaster that should be feared to a natural process that must be restored in the landscape. Across academic institutions, government agencies, and organizations, stewards of the land are working to restore fire via traditional burning practices, prescribed fire, and managed lightening-ignited fire – all as tools to reduce fuels and create resilient forests.

Fire Adapted Ecosystems

What do fire adapted ecosystems look like? California is home to a multitude of ecosystems, each defined by unique vegetative communities, geography, topography, histories, and fire regimes. A fire regime is a characteristic of a fire-adapted ecosystem and describes the frequency, season, and severity at which fires occur naturally.

For example, in Sierran mixed conifer forests, where summers are hot and dry and lightening strikes frequent, especially at high elevations, the natural fire regime would occur at a frequent interval from roughly June to October. Historically, prior to fire suppression tactics, these frequent summer fires would occur at low to moderate severities, burning surface fuels and ladder fuels like downed trees, dead branches, and small shrubs.

More infrequent occurrences of patchy, high severity, stand replacing fires also occurred on a longer return interval. Overall, there was a diverse mix of fire frequencies and severities with an estimate of 450,000 to 1.4 million acres burning every year in in California forests pre-European colonization, thereby creating a fire-resilient mosaic landscape.

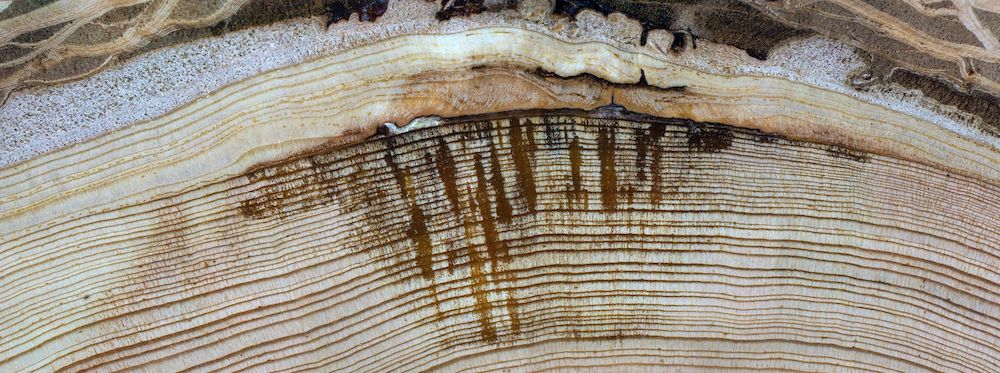

How can we know about a fire regime that occurred more than 200 years ago? There are certain plant adaptations that provide clear evidence of this. For example, many of the Sierran mixed conifer tree species have thick bark that protects the inner wood that the tree depends on for survival. Some conifer species even have serotinous cones, which are cones naturally sealed by resin that melt when heated by fire, thereby releasing seeds. Their presence indicates that the fire they need to reproduce occurred in that locale.

In addition to these fire-adapted characteristics, fire histories also can be obtained from many sources, including charcoal deposition records in soil, dendrochronology studies to date fire scars, fire modeling software, and consulting regional Tribes with traditional burning practices and Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Using all of these methods and more, historic fire regimes can be rebuilt and reimagined on the landscape scale.

Compared to the fire regimes that occurred prior to European colonization in the Sierra Nevada, the current fire regime can best be described as a fire scarcity. However, there is a critical distinction between the low- to moderate-severity fires that occurred prior to fire suppression practices versus the high-intensity fires that California has seen within the past two decades. These wildfires that claim lives, destroy people’s towns, homes, and businesses, and completely change whole ecosystems from forested to non-forested, are exactly the kinds of fire so many are working to avoid every fire season.

Such devastation has brought about a call to action, with efforts such as the newly released California’s Wildfire and Forest Resilience Action Plan from the Governor’s Forest Management Task Force. Prescribed fires, managed lightening-ignited fires, and cultural burning practices are only some tools of many being deployed to tackle the challenge of restoring resilience in forests and communities. We here at SYRCL are involved in some of these efforts to restore resilient forests through the North Yuba Forest Partnership, Yuba Forest Network, and Yuba Watershed Stakeholder Mapping Project.

There is a lot of work to be done to reach the desired condition of a fire resilient forest, and even then it will be an ongoing process. Land managers, decision-makers, and all of us who call the forest home must continue to adapt to the evolving story of fire and push forward towards resilient forests and resilient communities alike.

Contributor: Mary McDonnell, Forest Conservation Coordinator

Mary grew up near Sacramento, CA, spending summer vacations fostering a love for California’s many diverse landscapes. In college, she studied land management techniques, completing a major in Conservation and Resource Studies and a minor in Forestry from UC Berkeley. Mary has worked as a research assistant in range ecology and forest ecology, and as a land steward in an organization that conserves open spaces.

Mary arrived at SYRCL in the fall of 2019 as our AmeriCorps Restoration Coordinator. Last year, she accepted a full time position as our new Forest Conservation Coordinator.

Did you enjoy this post?

Get new SYRCL articles delivered to your inbox by subscribing to our ENews.