The Damming of the Bear River, by American Rivers

Article published May 18, 2017 by Max Odland, American Rivers Associate Director of Headwaters Conservation, CA

This post is a part of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Bear River.

Northern California’s Bear River is threatened by the proposed Centennial Dam, which would inundate six miles of the last publicly accessible free flowing stretches of the river.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll introduce you to a series of posts that explore different aspects of the Bear River, #2 on the list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2017.

WELCOME TO THE BEAR RIVER

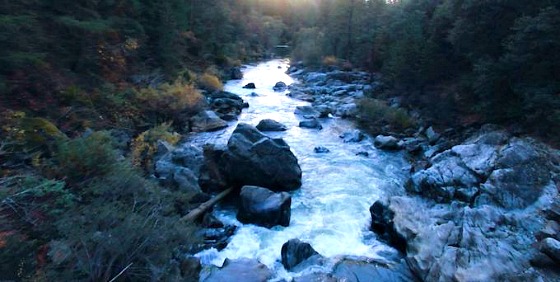

The Bear sits in an often overlooked watershed, nestled in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains, flowing 73 miles from rocky crags and conifer forests to the oak woodlands, open grasslands, pastures, and fields of the Central Valley.

When European-Americans first came to the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, everything changed; hillsides were washed away in the search for gold, and rivers were forever changed. The Bear was in the heart of that rush. Mining gave way to agriculture and, later, to residential development in the watershed.

The resulting water infrastructure leaves the Bear River impounded behind a series of dams over much of its course. Despite the history of heavy-handed manipulation (and perhaps even more so because of it), the remaining stretches of free-flowing water on the Bear River are a lifeline for local communities and wildlife.

The Bear River supports recreation, cultural use and rare habitat. Locals and visitors enjoy hiking, birdwatching, camping, angling, gold panning, rafting, and kayaking on the Bear’s four-mile class II whitewater run. The river is also home to numerous historic sites, including Native American Nisenan village and burial sites. Today, the mature mixed conifer and oak woodlands along the river are still used by Nisenan for plant collection and ceremonial purposes.

The river’s woodlands are an incredibly diverse ecosystem that provides habitat for an abundance of sensitive species, including California black rail, bald eagle, foothill yellow-legged frog, ringtail cat, and big-eared bat. The lower reaches of the river support a number of iconic fish species, including Chinook salmon, Central Valley steelhead, and green and white sturgeon.

You can find a more detailed account of the river and its history here.

WHAT’S AT STAKE?

The 275 foot tall Centennial Dam would flood the most popular river access points for recreation, along with dozens of Nisenan cultural sites and over a thousand acres of oak woodlands and riparian forest. It would turn six miles of flowing river into yet another reservoir in a nearly unbroken 17 mile chain of reservoirs in the middle reaches of the Bear.

The dam proponents, Nevada Irrigation District (NID), claim that they need to build the dam to overcome the challenges posed by climate change, and to meet growing water demands in the future. However, NID has not demonstrated that it is following best practices for water conservation and efficiency, or that the water to fill this new reservoir will be available in the Bear River watershed under predicted future climate conditions.

Further, NID’s own cost estimates for the dam have risen from $160 million to $500 million (a common occurrence with reservoir projects elsewhere in the country). Local community members have raised serious concerns that the anticipated costs of the dam would undermine needed repairs and more effective climate change management strategies, such as water use efficiency and optimizing existing systems.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

Across the country, communities have been rising to water supply challenges like drought, climate change, and growing populations with innovative water conservation and new approaches to water management. In many cases, they have been able to save considerable amounts of money compared to traditional water supply projects like new dams.

NID should work with the community and river advocates to pursue common-sense water conservation measures and alternatives that promote resilience to climate change without destroying invaluable natural, cultural, and recreational resources. A new dam should be the last alternative considered, not the first.

Fortunately, Centennial Dam must pass through many hurdles before construction, and faces multiple turning points in the next year from state and federal decision makers. It is imperative that organizations and individuals maintain pressure on NID and other key decision makers to reevaluate the need for this new dam.

Right now, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is conducting federal environmental review for the project, and has the authority to deny permits to build the dam. Join us in asking the USACE to deny permits for the dam in favor of alternative actions that would improve water security in light of a changing climate, while preserving and enhancing the rich natural, social, and cultural resources of the Bear River.

Did you enjoy this post?

Get new SYRCL articles delivered to your inbox by subscribing to our ENews.